Night and Fog in Japan and the Staging of Anti-Imperialism

Sunday, March 8, 2020 at 10:51PM

Sunday, March 8, 2020 at 10:51PM Julia Alekseyeva

[ PDF Version ]

Oshima Nagisa’s film Nihon no Yoru to Kiri (Night and Fog in Japan, 1960, Japan), the last he would make with the Shochiku film studio, documents a pivotal moment in postwar Japanese history without the use of any actuality footage[1].In lieu of newsreel documentation, it takes the form of what Sato Tadao calls a “discussion drama” or “drama dialogue,” in which two generations of student protest movements are allegorized and rendered theatrical[2].Through its idiosyncratic use of mise-en-scène and cinematography, Oshima’s film stages the rift between two anti-imperialist factions of the Japanese left: the Stalinist generation of the 1950s, known as the Old Left, and what would become known as the New Left, the younger students protesting the Japan-US Security Treaty, called ANPO in Japanese (Nichibei Anzen Hoshou Jouyaku), in 1960.

The operative word stage is no accident: Night and Fog in Japan is intensely theatrical in both form and narrative. Yet its formal theatrical elements are not decorative but instead distinctly modern, evoking the austerity and drama of a Brechtian play. The political speeches recited by the film’s protagonists are likewise consciously performative. The film takes place during a single wedding ceremony during which friends are called upon to make speeches. This ceremony unveils a microcosm of Japanese anti-imperialist movements, exposing their multiple rifts and contradictions to celluloid. In so doing, the film reveals not a unified leftist unit but a “season of schisms” (bunretsu no kisetsu) in the immediate wake of the 1960 protest movement[3].

The wedding in question takes place immediately following the June 1960 ANPO protests and includes occasional flashbacks to the Zengakuren protests ten years earlier. The Zengakuren, a massive student organization, recruited from 272 universities that involved 200,000 students from across the country, was born in the immediate postwar years. As Annette Michelson notes, Oshima’s anti-imperialist politics were formed precisely in this postwar period, an era defined by constant internal debate and factionalism. It was in the struggle of 1959–60, against the ratification and implementation of ANPO, where this movement reached its culmination[4].

While these two generations of protest movements differed in their ideological bent, they were united in their opposition to American violence and hegemony. As the Cold War progressed, the US attempted to use Japan strategically to keep communism at bay. Although Article IX of the Japanese constitution, which outlawed war as a means of settling international disputes, prevented Japan from participating in military endeavors, the immensely controversial ANPO treaty allowed the United States to maintain military bases on Japanese soil. Japanese leftists of all generations knew that, although Japan held a global image as a peaceful nation in the wake of the catastrophe of the Second World War, its reality, especially following its own history of fascism and imperialism, revealed nothing of the sort.

These two pivotal moments in postwar Japan—the factionalism and infighting of the Zengakuren protests, and the ANPO struggles ten years later—are dramatized by the events in Night and Fog in Japan. These movements and schisms are personified by certain characters, and political interrelations are frequently represented by personal, and often sexual, liaisons. Love triangles, adultery, and spurned lovers abound, unapologetically wedged between discussions of Marxist criticism. As is common in Oshima’s filmography, the political is allegorized in the personal.

The blend of psychosexual and socio-historical is so ingrained that the characters constantly conflate the two in often quite macabre ways. For instance, the wedding that frames the narrative unites two activists: one former student of the Zengakuren generation (Nozawa Haruaki), and one current, younger student coming of age during the ANPO protests (Harada Reiko). The lovers first meet in the midst of the bloodiest day of the ANPO struggle: on 15 June 1960, during which a student (Kanba Michiko) was killed by riot police while storming the south gate of the Diet[5]. As Professor (and wedding emcee) Udagawa states in the film, “Their [the new married couple’s] future will be bound to the destiny of the Japanese race.” Their marriage is an act of political consciousness—a sign of hope that two generations of communist students will join hands in collective struggle. This, of course, does not go exactly as planned. Throughout the film, the marriage between Nozawa and Reiko is not presented as a result of sexual desire, or even of friendship, but rather as a symbolic political gesture[6]. Nozawa states that he became attracted to Reiko specifically because of his nostalgia for student protest movements, without listing anything particular to Reiko per se. To this, Professor Udagawa adds, “June fifteenth marked the beginning of a new postwar era in Japan,” making the fact that the couple met in the midst of riot gear and bloodshed especially symbolic. Their marriage embodies the strife and tension between two generations of leftist student protesters in the new postwar era. Yet Nozawa and Reiko are not necessarily presented as equals; Reiko has nothing much to gain from marriage, while Udagawa hopes that Nozawa will “absorb the energy of the current movement” from being married to Reiko. The term absorb is particularly chilling and evokes a bizarrely literal embodiment of political experience. One cannot help but wonder if Nozawa, upon absorbing Reiko’s youth and spirited political engagement (ostensibly through sexual intercourse), will end up curbing Reiko’s political desires, instead of receding—as two members of the Zengakuren generation, Misako and Nakayama, allegedly have—into the so-called comforts of domestic bliss[7].

The characters of Night and Fog, especially those of the older generation of students, unearth repressed political memories of the Zengakuren protests during the ANPO protests ten years later, making this newly inspired political drive an unconscious rehearsal of earlier trauma. Igarashi Yoshikuni traces the Zengakuren’s behavior during the ANPO protests back to a desire to “[release] old experiences and emotions, which for a long time they could not have rendered in words[8].” As he notes, seeing the resurgence in political activity among contemporary students “pierced a deep, only semiconscious layer of the people’s spirit[9].” The term semiconscious is particularly apt. Although the Zengakuren like Nozawa (formerly a student, now a journalist), are conscious of their desire to restage the protests of the immediate postwar period, they are unable to articulate this desire fully. Thus, Nozawa cannot just participate in the protests and lend a helping hand; he also feels the need to marry a young participant as a way of normalizing and rationalizing highly complex subconscious political experiences and emotions. Igarashi might have also added that this restaging of protest movements is not solely due to semiconscious thoughts, but also a deep sense of guilt over the outcome of the Stalinist approach that Nozawa originally supported. In the film, his guilt over inadvertently causing fellow student Takao’s suicide resulted in this desire to reenact the past. When applied to the ANPO protests, the term repression is not merely a sexual repression, but a repression of deep-seated drives to political engagement, for which Japanese citizens had no outlet for almost a decade.

For Oshima, a fitting representation of these deep-seated drives for both political and sexual freedom would involve more experimental formal techniques. Importantly, these techniques explicitly criticize Stalinist socialist realist aesthetics, thus carrying over Oshima’s critique of Stalinism through both the film’s form and narrative. In Night and Fog in Japan Oshima attempts a “new method of perpetual active involvement” by experimenting with theatricality, using modernist formal methods whose very nature reinforces the political content expressed therein[10].

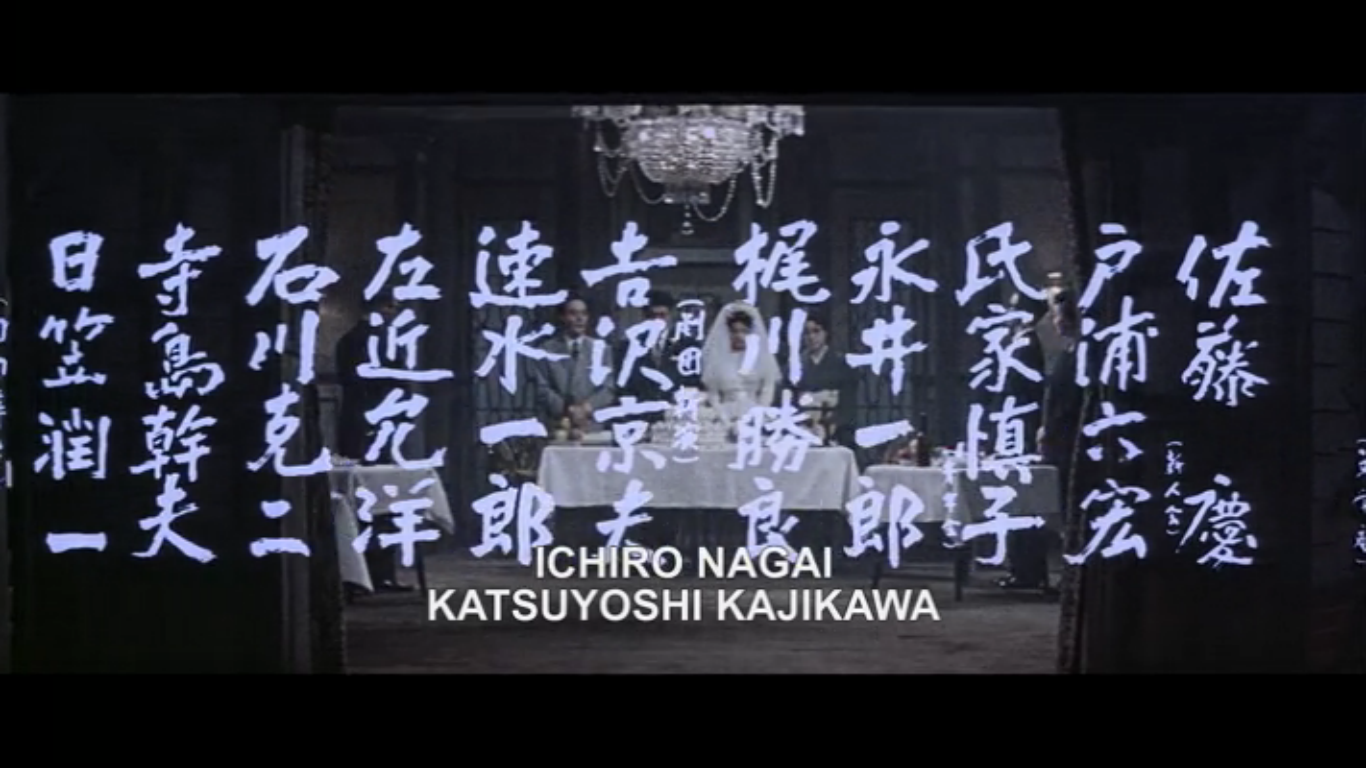

The film begins with the camera panning slowly into a room, employing one-point perspective by zooming into a vanishing point in the center of the frame. Not only do (window) curtains literally frame the shot, the credits hover over this frame, creating a palimpsest of imagery and also acting as a second curtain, which rises as the camera zooms into the room.

Figure 1. Wedding Curtain Credits.

As we enter between the two curtains, and as the credits slide past, the metaphorical curtain of the theatre lifts as well, and we enter into a ritualized, ceremonial space: a wedding.

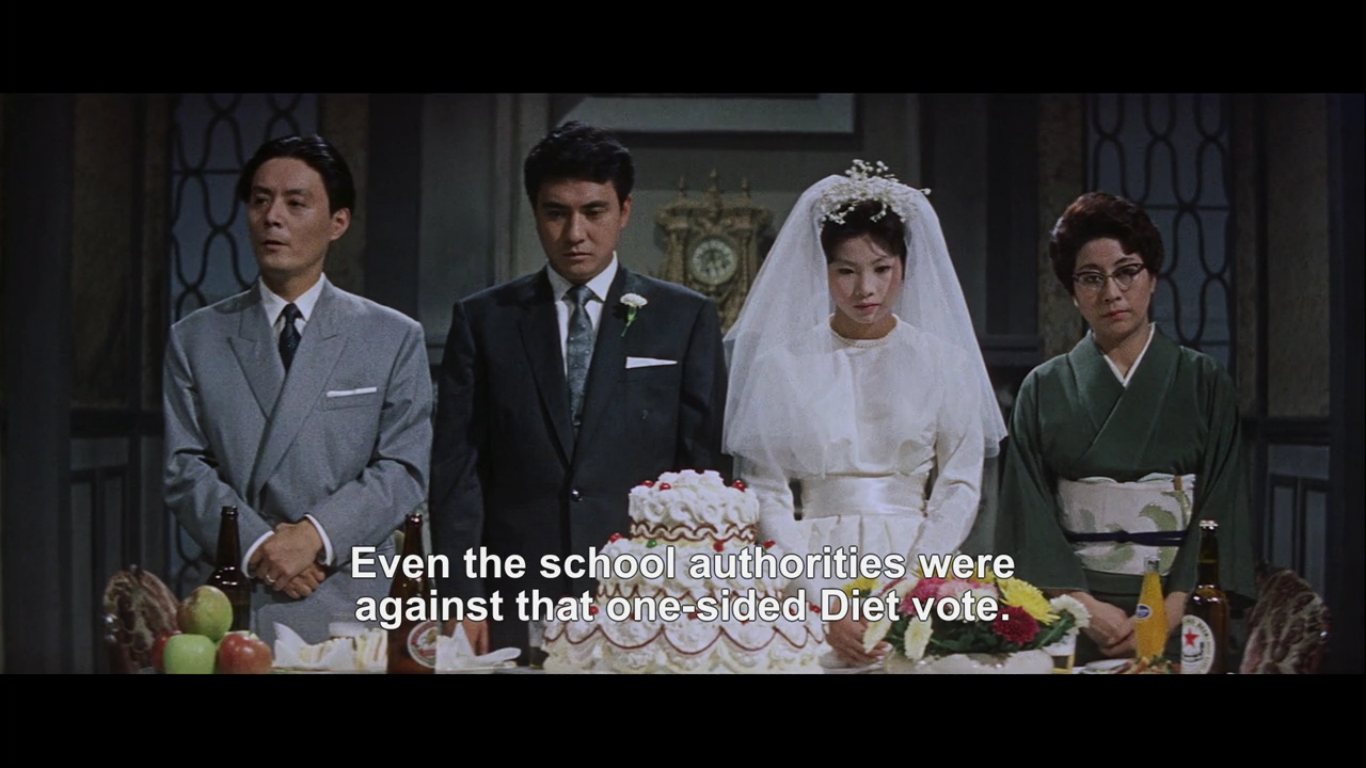

Although the film employs flashbacks, its diegesis remains constrained to the space of this single wedding reception, mimicking the temporal constraints of plays. Similarly, evocative is the use of symmetry, demonstrated by the film’s highly geometrical mise-en-scène. During the first few moments, as we are brought into the space of the wedding reception, the frame is divided up equally between four characters, with the men on the left and women on the right.

Figure 2. Wedding Party.

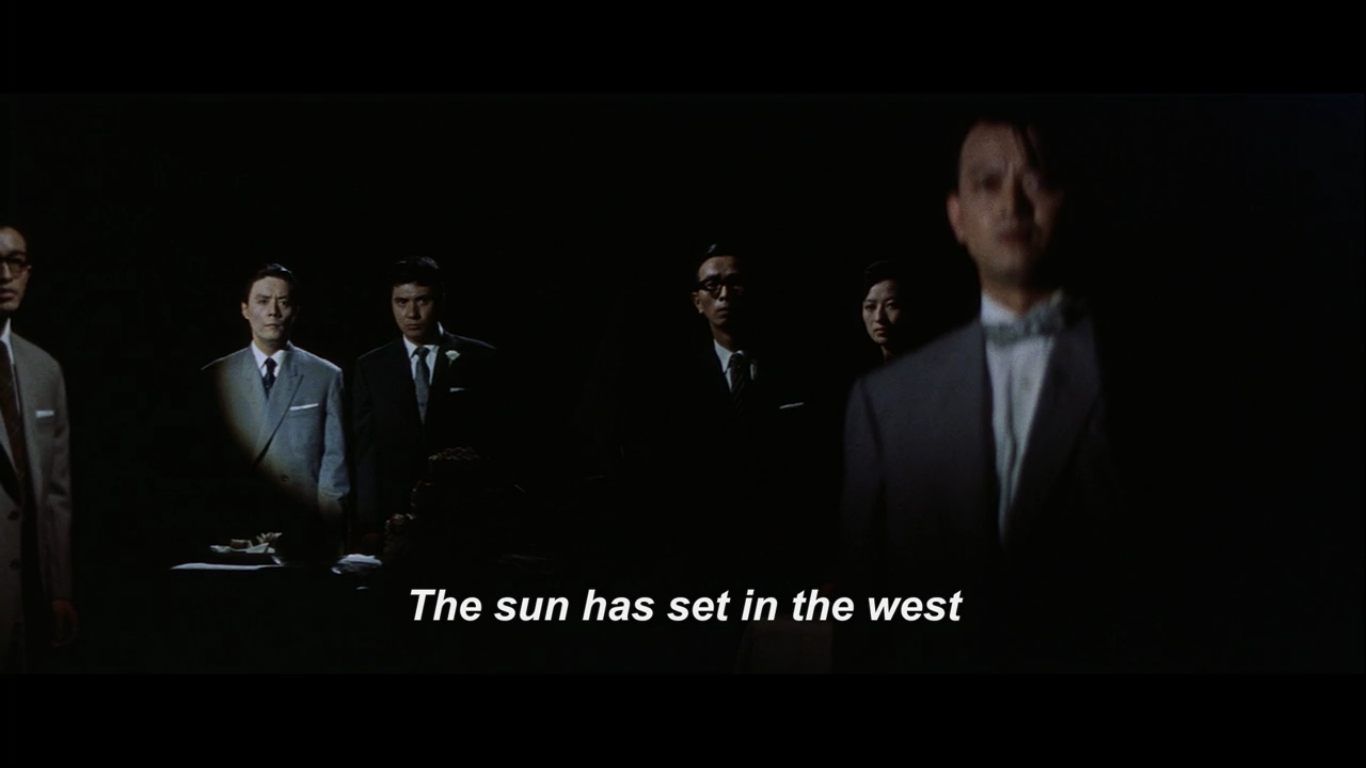

Likewise, the use of lighting in the film frequently evokes the spotlight of a theatrical production. Going beyond standard conventions of studio films, Oshima creates an otherworldly atmosphere by placing the spotlight on certain characters during pivotal moments—for instance, highlighting the faces of the June 15 ANPO protesters (including Nozawa and Reiko), or placing a single character in the center of the shot while the rest of the frame remains pitch black.

Figure 3. Spotlight on Group.

Figure 4. Spotlight on Reiko.

Conversely, the spotlight also serves, when dimmed, to transition between scenes, throwing whole spaces and characters into complete darkness, again evoking the techniques of a play at the end of each scene. The intrusion of this jarring spotlight serves to unmask what had heretofore been left suppressed: social relationships, in all their complex interweaving geometries, are placed into meaningful positions within a frame, and frozen still. The spotlight, aided by the occasional freeze-frame, allows the audience to cognitively map the relationships between characters and their roles in Japan’s leftist political spectrum.

Finally, Oshima’s film is strikingly theatrical—and equally anti-cinematic—in its extreme lack of montage. The film includes very few cuts. According to Oshima, the film has only 43 shot-sequences[11]. Instead, the film incorporates pans, tracking shots, and long, sustained takes; the camera is extremely mobile, quickly moving from one character’s face to another. This constant use of the tracking shot evokes the eyes of a spectator watching a theatrical performance. Parting ways with the basic tenets of early Soviet film theory, and departing especially from the techniques of Sergei Eisenstein, Oshima’s film instead highlights the drama inherent in each shot. Oshima does not aim to horrify or disturb, but to disorient. Notably, compared to Eisenstein’s cinematography, his own appears remarkably understated. Slow, careful panning allows the viewer to reflect upon the political ramifications of each scene at their own pace.

Yet even as the film stages a series of discussions about Marxist theory, aside from a strong critique of Stalinism, its politics remain curiously undefined. It does not fully embrace the Japanese New Left, instead choosing a more critical framework. In its lack of montage and the fundamental porousness of its politics, the film investigates, embodies, and acts out the contradictions within Marxist anti-imperialist movements in 1960s Japan. As Takumi states during the wedding reception, “How can you build a united front if you don’t deal with conflicting ideals?” In much the same way, the film attempts to lay bare these selfsame conflicting ideals within Japanese anti-imperialism during the ANPO protests of 1960, as well as in postwar leftism in general. When Takumi states to Nakayama, “You lack political sincerity, the desire to listen to the whole truth,” this becomes an attack on the Old Left more broadly.

Importantly, Night and Fog in Japan equates Eisensteinian montage with the Old Left and a Marxism which appeared woefully old-fashioned by the 1960s. In the 1960s, certain filmmakers worldwide, including Jean-Luc Godard as well as Oshima Nagisa and Matsumoto Toshio, perceived Eisenstein somewhat unfairly, as kowtowing to Stalinist aesthetics. Eisenstein’s concept of dialectical montage thus became intertwined with Stalinism as a whole. The tracking shots, spotlights, and symmetrical mise-en-scène in Oshima’s film distance themselves from Eisensteinian montage, and by so doing, draw further away from socialist realist aesthetic techniques. Thus, the film attempts to lay bare the rhetoric of socialist realism and unmask the political unconscious of what Ota, a representative of the radical New Left in the film, describes as the “wrecks and cripples haunted by the ghost of Stalin.”

By using these experimental formal elements, Oshima creates a space for openness, critique, and political freedom in what is essentially a “filmed ideological treatise” (shiso ronbun)[12]. For a certain number of experimental Japanese filmmakers in the 1960s, and especially for Oshima, reality was not accurately reflected through purely realistic modes. However, the solution was not an intensely decorative and ultra-aestheticized filmmaking, but one which criticizes the ubiquity of a realism associated with the Old Left. If Oshima’s Night and Fog in Japan strove to interrogate the spectator and allow them to analyze Japan’s contemporary historical moment, it is through the aid of Oshima’s formal devices—especially through the synthesis of narrative fiction and documentary, and the critique of realism[13]. Oshima, in his attempt to avoid what he termed a “fake dressed up to look like the real thing,” relies on the experimental; a blurring of genre boundaries and a relaxing of narrative codes[14]. Eschewing both socialist realist filmmaking and strict actuality footage, his film uses the genre conventions of modernism, especially modernist theatre, to highlight the potential of film to disorient, estrange, and emancipate. In Rancière’s terminology, and following Brecht, Oshima desired to create active participants as opposed to passive voyeurs[15].

However, one must note that Oshima does not provide any solutions to the historical and political questions he raises, and the film concludes on a deeply disturbing note of complete powerlessness. In the end, even when all relationships—personal and political—are laid bare, even when the political unconscious has been unmasked, nothing has been accomplished, and Nakayama’s Stalinist rhetoric fades to voice-off while the frame is enveloped in darkness and fog. Sixty years later, Oshima’s film seems eerily prophetic: the protests would soon subside, replaced with increased nationalistic fervor; Japan would find itself swept up in preparations for the 1964 Tokyo Olympics, before an even more radical resurgence in revolutionary politics in 1970. Echoing the fate of the ANPO protests, Night and Fog in Japan was removed from circulation before even completing its first run. The film was withdrawn on 12 October, the same day as Asanuma Inejiro, a socialist politician, was assassinated by a right-wing extremist[16]. Night and Fog was thus drawn inexorably into the fate of the political system it sought so earnestly to represent.

Notes

[1] Nihon no yoru to kiri (dir. Oshima Nagisa, Japan 1960), produced and distributed by Shochiku Company Limited. Translated Title: Night and Fog in Japan (the title is a reference to French New Wave director Alain Resnais’s short 1955 documentary Night and Fog about the Nazi concentration camps).

[2] Sato Tadao, Currents in Japanese Cinema, trans. Gregory Barrett (Tokyo: Kodansha International, 1982), 49.

[3] For a detailed explanation of the “season of schisms,” see Nick Kapur, Japan at the Crossroads: Conflict and Compromise after Anpo (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2018).

[4] Annette Michelson, “Introduction,” in Nagisa Oshima, Cinema, Censorship, and the State: The Writings of Nagisa Oshima 1956-1978 (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1992), 4.

[5] Wesley Sasaki-Uemura, “Competing Publics: Citizens’ Groups, Mass Media, and the State in the 1960s,” positions 10, no. 1 (Durham: Duke University Press, 2002), 90.

[6] Although these characters’ full names are Harada Reiko and Nozawa Haruaki, I’ve retained only the former’s first name and the latter’s last name because this is how they are referred to most often in the film (although I am aware of the misogynistic connotations of calling women by their first name and men by their last, especially in the same social context).

[7] The vastly different representation of male and female subjects in the film is no accident, and Oshima was quite conscious of the different roles expected of men and women in this time of social repression. As Sasaki-Uemura writes, during the ANPO protests, activists perceived a gender separation and tension between a predominantly male Marxist movement, and a more women-oriented movement based on quotidian issues. This traditional gap between the male realm—devoted to public activity and protest organization—and that of the female realm, devoted to issues of marriage and daily life—is even evident in the use of first names for women and last names for men throughout the film.

[8] Yoshikuni Igarashi, Bodies of Memory: Narratives of War in Postwar Japanese Culture, 1945-1970 (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2000), 139.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Michelson, Oshima, Cinema, Censorship, and the State, 48.

[11] Ibid., 49

[12] Isolde Standish, A New History of Japanese Cinema: A Century of Narrative Film (New York: Continuum, 2005), 256.

[13] Ibid.

[14] Oshima, Cinema, Censorship, and the State, 42.

[15] Jacques Rancière, The Emancipated Spectator, trans. Gregory Elliott (London: Verso, 2009), 3–4.

[16] Standish, A New History of Japanese Cinema, 256.

Julia Alekseyeva is Assistant Professor of Cinema and Media Studies and English at the University of Pennsylvania. Her work researches global media and radical politics in Japan, France, and the Soviet Union. She is currently working on her first academic monograph, on semi-documentaries in the French and Japanese 1960s.