The Geopolitics of Narrative Parody in Ulrike Ottinger’s Johanna d’Arc of Mongolia

by Maggie Hennefeld

Ulrike Ottinger’s feminist New German film Johanna d’Arc of Mongolia (1989) addresses the geopolitical decentering of national identity through its parodic construction of narrative space. The film depicts the plight of a Trans-Siberian Rail tourist train whose hijacking by a nomadic tribe of Mongolian women coincides with the film’s own generic reversal: at this halfway point, the style transitions abruptly from postmodern, self-reflexive theatricality into a serious mode of ethnographic documentary. The Mongolian tribeswomen abduct an all-female group of bourgeois European tourists—including nineteenth century amateur ethnologist Lady Windermere, musical performer Franny Ziegfeld, and German secondary school instructor, Professor Mueller Bohwinkel—and then lead these women out into the steppes to observe the unfolding of nomadic Mongolian culture. The intertextuality of the train’s anachronistic patronage represents a sense of historical flatness that mirrors the mythical timelessness represented by the Mongolian tribeswomen. The film’s own construction of narrative space—aesthetically self-quoting to an absurd extent while on the train, but anthropological and unimposing while out in the steppes—provides a framework for grappling with its critical commentary about the codification of spatial representation in both fictive and documentary genres.

It is helpful to think of the Trans-Siberian train, where the postmodern pageantry of the first half of the film unfolds, as a metaphor for the status of documentary evidence in the film as a whole. The question of the image as a form of evidence and its relation to documentary aesthetics opens onto larger issues for our current historical moment: whether the image still bears any relation to the referent whatsoever. The ability of a documentary film to center its spectator by constructing an illusory sense of spatial positioning vanishes with the withering of the referent. Paradoxically, belief in the image has traditionally been shored up by a diverse range of manipulative narrative techniques, from Robert Flaherty’s restaging of outmoded Eskimo traditions in Nanook of the North (1922) to the commodification of supernatural belief in The Blair Witch Project (dirs. Daniel Myrick and Eduardo Sánchez, 1999). The absurdist proliferation of unanchored signifiers, both nationalist and cine-aesthetic, on the Trans-Siberian train attempts to stage a confrontation between the status of belief and its manipulative construction in documentary practice. Spectatorial decentering often refers either to avant-garde modes of critical foregrounding or to the aesthetics of late capitalism and its spectacular commodification of self-reflexivity (pastiche and hollowed-out irony).[i] Here, the spectacle of multiculturalism that mobilizes the film’s parody brushes up against the film’s experimental documentary aesthetics: its insistent foregrounding of the camera’s subjective limits to provide a centered position for its spectator.

The camera’s drive to represent spatial depth, which would reinforce the image’s status as a form of cultural evidence, provides an impetus for its wandering looks. Cinematography in the opening section of the film is driven by the camera’s persistent inability to construct images of depth in space—a frustration that aestheticizes the absurdist and anachronistic proliferation of multicultural identities on the train.[ii] The train’s intertextual clientele, which ranges from 19th century literary characters, to folk story archetypes, to present day Mongolian motorcyclists, evokes Arjun Appadurai’s description of postmodernism’s flattening of historical time: “a synchronic warehouse of cultural scenarios, a kind of temporal central casting.”[iii] The camera takes up an aesthetics of wandering from the film’s opening images.

In contrast to the on-location shooting in the Mongolian wilderness during part two, the film commences by marking the imaginary impossibility of its own “outside”; the exterior landscapes on the other side of the train windows are represented with blatant stage sets, as if plucked from the mise-en-scène of a 1920s German Expressionist film. The train’s industrial penetration of the Siberian landscape is thus marked from the beginning as simultaneous with its own histories: global multiculturalism displaces the sovereign conquests of imperialism. Revealingly, this already-marked textual surface projected globally from the train’s “inside,” opens from the space of a first-class passenger car—with the ongoing dissolution of barriers between “first” and “second” worlds, nothing stands between the globe and its imminent commodification. In this scene, the camera takes its cues from material traces in the diegetic landscape, spatially mimicking unexplained tears in the walls, and returning several times to a wall-mounted map of the world. Despite the kinetic impetus that these objects transmit, they do not provide the camera with enough traction to explain or to orient the space that it seeks to construct. They represent clues without evidence, a documentary slippage of signifiers with no logical conclusion.

However, I would argue that the dual processes of decentering that take place between the train’s postmodern spectacle and the camera’s aesthetic foregrounding in fact construct a sense of positionality that they would otherwise seem to deflect. The film’s documentary scrutiny of its own spatial impossibility works to create a meta-narrative about the slippery aesthetics of late capitalism. Humor, especially parody and its proliferation of mimesis, plays a key role in this pursuit. According to the definition provided by Henri Bergson, the comic asserts a non-mimetic relationship between film objects and viewing subjects by provoking audience laughter in response to (and often at the expense of) profilmic images.[iv] Lady Windermere’s (Delphine Seyrig) disembodied voiceover during the opening exhibition of her passenger car provides a historical narrative for grappling with the complex dialectic among the different forms of humor at play during part one—which do not disappear even during the ponderous on-location long-takes of part two. Windermere thinks about the semiotic implications of Siberia’s historical encounters with the West: “In 1581 Yermak Timofeyevich traverses the Urals with his ferocious Cossacks and sees for the first time … things read—the imagination—the confrontation with reality. … Must imagination shun the encounter with reality, or are they enamored of each other? ... Does the encounter transform them?” The knowledge and insight represented by Windermere’s “voice from nowhere” provides a crucial framework for grappling with the geopolitics of cultural transformation between cinematic images and their material referents. The global decentering of national identity and concomitant displacement of subjective positioning buttress a waning of belief in the image: its ability to carry any relation to a referent. Further, the absurd disjuncture between Windermere’s narrative voice and her body’s profilmic presence during this scene itself functions as a parody of the voice-over’s truth-telling status in the documentary genre.

The function of humor to construct an awareness of spatial difference in this film is complex and requires close reading. The differences at stake in the film’s slippery aesthetics of depth refer to multiple interlocking entities: the self-difference between Germany’s present conjuncture (1989) and its “unspeakable” histories; the ability to demarcate geopolitical distinctions with the imminent fall of the Iron Curtain; aesthetic differences between contrived and “authentic” styles of filmmaking (i.e. the campy train sequences as opposed to on-location shooting); gender identity politics intrinsic to the cut between the two parts of the film, the latter half of which features women almost exclusively.[v] When difference as such is effaced by the fantasy of pluralism, the realities of subsumption become increasingly thornier to detect.

Mickey Katz dining scene on train

In a parodic musical theater performance on the train, international Jewish vaudeville star Mickey Katz[vi] (a throwback to the ‘20s Hollywood icon-in-black-face, Al Jolson) and the Kalinka Sisters (a Yiddish version of the Andrews Sisters) perform a rousing rendition of Jolson’s “Toot-Toot-Tootsie, Goodbye” to the delight of the train’s passengers. This resurrection of the history of Hollywood fantasy enlists the film’s heterogeneous aesthetic strategies to restage the awareness of difference that its performance simultaneously effaces. For example, throughout the number, the disproportionately enhanced scale of (already rotund) Katz’s swaying figure threatens the camera’s ability to register the presence of the Kalinkas’ separate bodies Yet, through an uncanny awareness of the limits of the frame, which differ substantially from the edges of the actual stage, the Kalinkas repeatedly crane their necks and stretch their limbs to subvert their encroaching erasure from the image. The Kalinkas’ comedic gesturing, which first appears as just an imitation of Katz’s Jolson parody, in fact becomes the hinge of their diegetic autonomy from Katz’s dominant position in the foreground. Moreover, this construction of a spatial difference between separate bodies opens onto the critical distinction between parody and the postmodern category of pastiche. Fredric Jameson describes pastiche as “like parody, the imitation of a peculiar or unique, idiosyncratic style…But it is a neutral practice of such mimicry, without any of parody’s ulterior motives, amputated of the satiric impulse, devoid of laughter and of any conviction...A statue with blind eyeballs.”[vii] The identity politics of the Kalinkas’ crucial assertion of spatial depth, which perhaps foreshadow the gendered implications of the film’s stylistic self-difference in part two, signify an epistemological depth within the film’s humorous proliferation of different historical modes and styles. (The humorous effect of how the train’s passengers all communicate in at least five different languages without ever encountering translation difficulties further represents the film’s critique of its own impulse toward pastiche—in other words, its insistence on parody.)

The parodic evidence constructed within the train’s theatrical landscape, its repeated attempts to assert depth against the train’s multicultural spatialization of history, are both complicated and intensified by the film’s stylistic transformation. At the fulcrum of the film vehicle’s reflexive journey (the clichéd link between the train’s geographic movement and its narrative self-discovery), on the cusp of exhausting its own ability to narrate itself, the train’s multicultural mobility gets hijacked. A nomadic herd of Mongolian tribeswomen abduct an eclectic and all-female group from among the train’s passengers, including Windermere the narrative voice, Ziegfeld the singer, and Bohwinkel, whose Baedekker guidebook becomes an “invaluable” source of trivial geopolitical knowledge during part two. In vividly absurd but thematically parallel contrast to the postmodern, multicultural pageantry on the train, the second half of the film takes a sobering look at the ethnographic politics of cultural duration. The numerous long-takes that unfold across the landscape of the steppes reflect the longstanding cultural traditions practiced by the nomadic Mongolian tribeswomen. These include a thirty-minute-long bow-hunting sequence, the preparation of the Mongolian culinary staple, salted yak’s milk, and a mythical eruption of the landscape itself.

According to Professor Mueller Bohwinkel’s Baedekker tourist’s guidebook, this earthquake is caused by a mythical spirit, who lifts up the turf to expose a buried earth hut wherein demons reside. However, Bohwinkel herself is mystified by how the shaman could have provoked this eruption during the summer. In this scene, the camera’s unintrusive long-takes slowly cut between a magnificent drum dance performed on the raised earth huts by the Mongolian women, and the tourists’ sideline spectatorship. Bohwinkel puzzles over the mystical temporality of this out-of-season earthquake while advising Windermere to offer her cutlery set as a gift for their Mongolian hostesses. Here, the camera’s ethnographic style in a sense parodies its own impulse to document Mongolian cultural tradition (which Ottinger actually does capture at length in a subsequent ethnographic documentary film, Taiga) by anthropologizing the tourist women’s reactions to the Mongolian earth hut dance.[viii] In this sense, the film continues to develop humor as a form of documentary evidence: the tourist characters’ rather absurd presence testifies in advance to the film’s own imminent commodification of Mongolian cultural history.

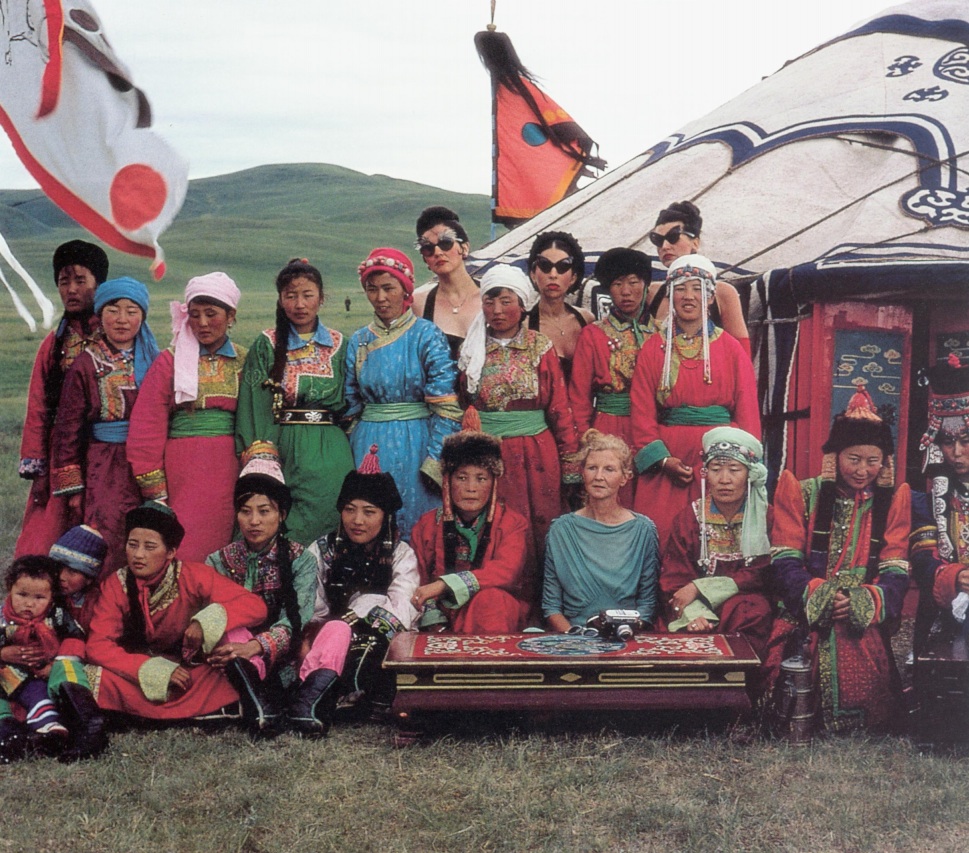

Mongolian Nadam festival in the grasslands

Again, in contrast to the camera’s recurring self-exposure on the train, during this unfolding spectacle in the steppes, the camera itself remains removed and impartial. Ottinger’s direct cinema approach here attempts to efface the presence of the camera entirely. Instead, the camera allows events to unfold within the film’s extended long-takes across the Mongolian terrain. The idea of creating a documentary ethnography of an entirely fictive and staged situation requires significant unpacking. Indeed, this fact belies any interpretation of the film that would romanticize its Mongolian ethnography as the binary opposite of its Trans-Siberian pastiche.

The lure of capturing Mongolia’s traditional coherence and continuity must be understood within its specific German national and historical contexts. Ottinger’s film Johanna d’Arc of Mongolia arrived at the tail end of the New German Cinema movement (NGC). Popularized by film auteurs such as Herzog, Fassbinder, and Kluge, the NGC sought to politicize the traumatic landscape of Germany national memory through its self-conscious filmmaking style. However, despite its challenging heterogeneity, by 1989, New German Cinema’s textual form had arguably become codified in the eyes of many of its viewers. In New German Cinema: A History, Thomas Elsaesser explains how a number of German directors responded to the burden of national representation with auteurist self-projection and stylistic self-parody. Although it is problematic to map out a coherent historical trajectory for the diverse body of films encompassed by the New German Cinema, this film movement generally progresses toward higher degrees of self-referentiality and self-parody. According to Elsaesser, “By the beginning of the 1980s … the New German Cinema had in effect established a thematic and social space where its films could be seen as formally coherent and historically determined.”[ix] In order to realize its critical ambitions of innovative self-expression, the New German Cinema’s self-parody emerged by the 1980s as an increasingly appealing means of formal expression.

I would argue that Johanna d’Arc’s satirically abrupt transition from postmodern parody to serious documentary functions as an implicit critique of the New German Cinema’s non-identity with its own film subjects by the late ‘80s. Parody had become a placeholder for the mode of critique intrinsic to the New German Cinema’s project; it functioned as a flight from the burdens of historical and national self-representation. “Some reacted to the commodity status of their products by an excess of personality, and often parody, in order to escape their mandate as ambassadors of Germany asked to legitimate German culture: reactions which can be studied in the films themselves.”[x] By troubling the very difference between parody and other more “serious” forms of cinematic representation, such as Mongolian ethnographic documentary, Johanna d’Arc attempts to reassert a relation between German national memory and recent formal developments in New German Films. In other words, Johanna d’Arc’s use of satire to critique the NGC’s by now codified non-self-identity functions to engage painful and buried questions regarding German cinema’s ability to grapple with its own traumatic national histories. Post-war attempts by German art film directors such as Herzog and Fassbinder to represent the exceedingly uncomfortable question of German national identity had reached an impasse by the time of Johanna d’Arc of Mongolia’s March 1989 release in West Berlin.

Theatrical Release Poster for Johanna d'Arc of Mongolia

Johanna d’Arc’s stylistic bipolar disorder itself foregrounds the problem of how any cinema mediates its self-identification—both cultural and subjective. In the first half, the camera’s desire to establish a subjective anchoring point by mobilizing the spectator’s escapist immersion in the diegesis itself lacks an anchoring point. The camera simply refuses to cut up space for the narcissistic projection of pleasurable identification, instead oscillating between relative stasis and profilmic imitation. Like the traditional narrative film spectator, the camera is literally paralyzed by its own desire to become more and more like that which it sees. Repeatedly throughout the film, the camera demonstrates its own parody of narrative film conventions by recording intimate conversations visually at a distance and from behind a large wooden beam. By internalizing the voyeuristic desires of the classical film spectator, who revels in the illicit pleasures of the look by identifying with a camera that itself remains concealed, the camera in Johanna d’Arc mimics a subjective position for the spectator.

By contrast, the interventions of the camera in the second half of the film all but disappear. If the camera on the train takes the question of cinematic identification to its limits, the camera in the steppes attempts to do away with the problem of identification altogether. In the context of the national identity issues that haunt much of the post-war German cinema, the film’s structural fragmentation engenders a new language for grappling with the present absence of National Socialism repressed by and within German culture and cinema. In the multicultural space of the train, the hyper-identifications of the camera in a sense internalize the post-national rhetoric of borderless, trans-global identity flows. During the second half of the film, however, the flight of the camera from the problem of its own mediation finds justification in the seeming national continuity and coherence represented by Mongolia: the fantasied space of the ethnic other. Indeed, Johanna d’Arc, the split subject of its own cinema, ultimately makes the point that neither form of escapism—scopophilic or ethnographic—can suppress the return of its own self-identifications. History erupts from inside of the seams of this thoroughly heterogeneous text.

As soon as Princess Ulun-Iga and her gang hijack the Trans-Siberian train by heaping a mound of sand in the middle of the industrial train tracks, all generic bets are off. I am tempted to read this traumatic arresting of the train’s mobility as an event that literalizes the return of repressed historical evidence: that is, the repression of the very fraught question of German national identity. It is only at this midway point that the film is able to imagine anything approaching the idea of national identity, a fantasy that gets projected onto the open spaces and longstanding cultural histories embodied by the nomadic Mongolian women. In other words, the coherence of national identity returns here through the ethnographic fantasy of Mongolia’s cultural duration: its very ability to represent its own history.

Theoretically, Ottinger’s stylistic transition in this film from “fiction” to “reality”—or from multicultural performativity to nomadic authenticity—was bound up in her broader gesture to play upon and to subvert audience expectations. What could be more contradictory than the codification of an experimental revolutionary cinema? Ottinger’s own cinema associated itself with the Berlin Film School, which advocated “a role for the cinema modeled on the one it had assumed after the Russian Revolution: that of a totally partisan instrument of agitation [and] political education.”[xi] Further, as Homay King notes in her reading of Johanna d’Arc of Mongolia, “Sign in the Void,” “critics hastened to mark” Johanna d’Arc as the fulcrum of “a ‘before’ and ‘after’ point in Ottinger's career.”[xii] Whereas earlier works by Ottinger such as Madame X: An Absolute Ruler (1978), Ticket of No Return (1979), and The Image of Dorian Gray in the Yellow Press (1984) adhered to a Berlin School ethos through their self-reflexive politicization of the camera, Johanna d’Arc seems to mark a stylistic inversion in Ottinger’s filmmaking both structurally and chronologically. Ottinger’s later works—The Arts-Everyday Life (1986), Taiga (1992), and Exile Shanghai (1997)—all employ the ethnographic documentary mode used to depict the Mongolian steppes in Johanna d’Arc.

However, rather than insisting on the irreducible difference between the two sides of Ottinger’s filmmaking politics, I would complicate this teleological mode of film history writing by pointing to the underlying questions that circulate across Ottinger’s oeuvre, and that map themselves onto both parts of Johanna d’Arc of Mongolia. The historical and national specificities of how Johanna d’Arc figures the question of cinematic identification appear to be in direct dialogue with the experimental New German Cinema’s creeping codification. The absent question of German national identity explicitly haunts the New German Cinema’s attempts to politicize the film medium’s aesthetic capacities, which it hoped to achieve by exposing and disrupting the escapist identifications facilitated by mainstream commercial cinema.

The camera’s anthropological mode of observation in part two captures the intertextual tourist women’s observation of Mongolian tradition with the same style of disinterested long-takes that it uses to document the Mongolian ritual earth hut dance or Princess Ulun-Iga’s salted yaks milk hand massage. This ethnographic approach to documenting its own imminent commodification of Mongolian history suggests the crucial role that humor continues to play during part two. Rather than positing Mongolian tradition as a cultural “outside” to the aesthetics of late capitalism (meanwhile circulating its Mongolian fascination within a Western economy of media images), the film’s persistent self-parody complicates its strictly observational style during its slower-paced, on-location sequences. Therefore, despite Johanna d’Arc’s ostentatious self-difference (its non-self-identity), the film’s inter-mediation between parody and ethnography significantly complicates the opposition between its two parts: between its parodic self-referentiality and its referential, self-effacing ethnography. The implicit displacement of Germany’s painful and buried national histories onto the Mongolian steppes serves as a potent reminder of parody’s political stakes. By reawakening parody’s “ulterior motives,” its impetus to negate its own history through persistent self-mimicry, Johanna d’Arc asserts the potential of self-parody as a crucial form of documentary evidence.

Notes

[i] Peter Wollen, "Godard and Counter Cinema: Vent d’Est," in Movies and Methods vol. 2, ed. Bill Nichols (University of CA Press, 1996), 500-508. Wollen posits foregrounding as intrinsic to any counter-cinema aesthetic. He defines this term as the refusal to make film language invisible, which would facilitate the pleasurable immersion of the spectator in an illusory film diegesis.

[ii] As outlined in the opening credits, the train’s passengers include: Articulate tenor of Yiddish American musical comedy stage; Russian officer; his adjudant in classical ballet of Bolshoi who broke off his training; Georgian ladies combo; 1 shaman with pupil; railway signalwoman; 3 spring maidens; Ludmilla a conductor on Trans-Siberian train; 6 Mongolian soldiers; 1 grandmother with goose basket; 2 ladies of the impoverished Russian nobility; 1 fur trapper; 1 proud goat owner; 1 head waiter with his garcons; 1 Russian ladies military band woman with Easter bread; ceremonial baker of the White Foods; Tscham dancers; lamas playing ritual music; Mongolian family in a motorcycle; 1 wise man with a horse fiddle; 6 sturdy Mongolian wrestlers; 6 female archers; 4 maids; 6 female lancers on swift riding camels; ladies in waiting to Mongolian Princess; August Monarch of the Grasslands and the Yurts.

[iii] Arjun Appadurai, “Disjuncture and Difference in the Global Economy,” in Theorizing Diaspora: A Reader, eds. Jana Evans Braziel and Anita Mannur (Oxford: Blackwell Publishing, 2003), 29.

[iv] “Comedy can only begin at the point where our neighbor's personality ceases to affect us. It begins, in fact, with what might be called a growing callousness to social life. Any individual is comic who automatically goes his own way without troubling himself about getting in touch with the rest of his fellow beings. It is the part of laughter to reprove his absentmindedness and wake him out of his dream.” Henri Bergson, Laughter: An Essay on the Meaning of the Comic (New York: Macmillan, 1911), 134.

[v] The thematic of female exclusivity is crucial to a number of Ottinger’s films. Madame X: An Absolute Ruler (1978) examines the sexual politics of contradictory female stereotypes in an intertextual feminist sea pirate scenario.

[vi] Katz is en route to perform for a diasporic Jewish community in Harbin, China.

[vii] Fredric Jameson, “Answering the Question, What Is Postmodernism?” in Postmodernism, Or, the Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism (Durham: Duke University Press, 1991), 17.

[viii] Ottinger’s eight-and-a-half hour documentary Taiga (1992) unintrusively captures everyday lifestyles in the Mongolian taiga regions in-between the steppes and the tundra.

[ix] Thomas Elsaesser, New German Cinema: A History (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1989), 279.

[x] Ibid., 6.

[xi] Ibid., 156.

[xii] Homay King, "Sign in the Void: Ulrike Ottinger’s Johanna d’Arc of Mongolia," Afterall Online Journal, No. 16 (Autumn/Winter, 2007).

Maggie Hennefeld is a Ph.D. candidate in Modern Culture and Media at Brown University. Her research interests include film theory, film historiography, humor, gender, and early cinema. Maggie has presented conference papers at ACLA, SCMS, and the 2010 Women and the Silent Screen conference in Bologna, Italy. Maggie’s journal publications include “The Aesthetic Politics of Hollywood’s Chain Gang in FDR’s America” (CUREJ, 2006) and “The Politics of Hyper-Visibility in Leni Riefenstahl’s The Blue Light” (forthcoming in Protéa, 2012). Maggie plans to teach a seminar on “Film Comedy” at Brown in Spring 2012. Maggie’s dissertation will focus on problems in film historiography and forgotten female comics of early cinema.

Media Fields Journal

Media Fields Journal